Is Attachment Theory An Overlooked Factor In Nurturing High Performance In Teams?

Attachment theory provides a useful yet underused framework for improving team dynamics in the workplace

Lifelong fans of any football (soccer) club will, given half a chance, recount at length who their favourite player(s) are or were from any era in their club’s history. (Don’t worry I’m not going to do that here. I promise to brief by way of introduction to this post 😇)

For me, as a fan of Liverpool FootbaIl Club, I would have to pick Jan Mølby and Trent Alexander Arnold as mine and for the same reason, they are highly gifted at seeing the ‘spaces in between’1 players that exist on the field of play and working with them to move the ball towards their opponent’s goal.

As it is on the field of play, so it is off the field in our places of work.

The ‘spaces in between us’ are fundamental to human life from our years as infants to the latter days of our lives in old age.

How we learn to navigate these spaces in between conditions how we relate to ourselves and others in any given context. Our ability to do this well significantly impacts a team’s ability to collaborate and perform at a high level and consistently achieve superior outcomes. In addition, doing this well

The Origins of Attachment Theory

Attachment theory, which explores the dynamics of long-term relationships between humans, has been studied extensively in various contexts, including its impact on human performance.

Attachment theory, pioneered by John Bowlby2 and Mary Ainsworth, suggests that early relationships shape how individuals form bonds and respond to others throughout their lives.

The theory, traditionally focused on the bonds between children and their caregivers, has been increasingly explored in various domains, including elite sports, leadership and academic performance.

The way we behave at work—especially in our professional relationships—has deeper roots than many business leaders realise. These behaviour patterns stem from early childhood experiences and were first identified through pioneering research spanning several decades.

In the 1960s and 70s, psychologist Mary Ainsworth conducted a series of simple yet revealing experiments called the 'Strange Situation'3. She observed how young children responded when their mothers left them briefly in an unfamiliar room and then returned. Through these observations, she identified three distinct patterns in how children formed emotional bonds.

The fourth pattern wasn't discovered until 1986 when researchers Mary Main and Judith Solomon noticed that some children showed confused, contradictory behaviours that didn't fit the original categories.

The discovery of the ‘disorganised attachment style’4 completed the picture of what we now know as the four attachment styles.

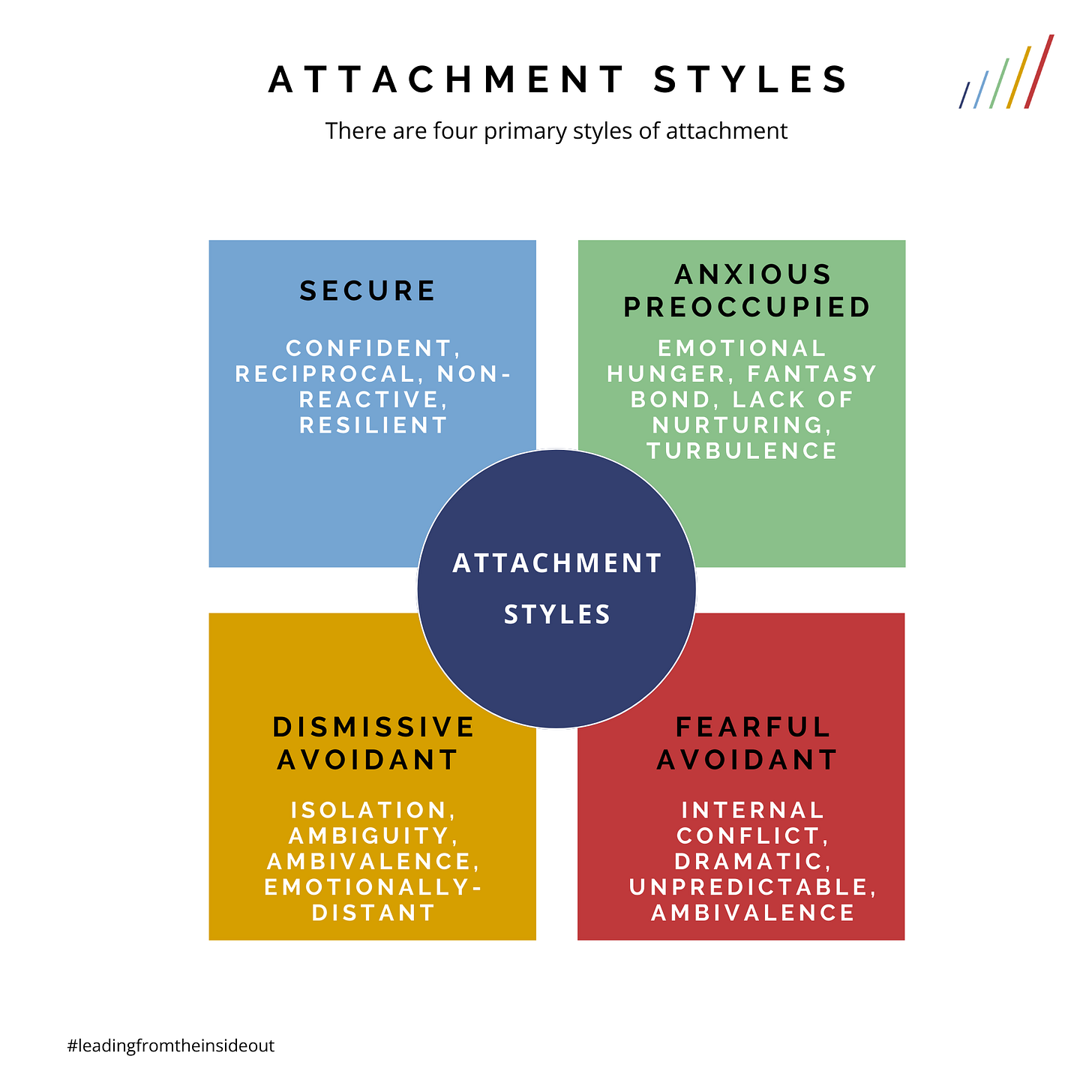

The modern framework, developed by Bartholomew and Horowitz in 19915, defines four styles that we see playing out in offices every day: secure (confident and collaborative), anxious-preoccupied (seeking constant validation), dismissive-avoidant (fiercely independent), and fearful-avoidant (unpredictable in relationships).

Attachment Theory In Workplace Teams

Recent research suggests these styles aren't fixed categories but exist on a spectrum, and people may show different patterns in different contexts6.

This flexibility is particularly relevant for workplace development, as it suggests that with the right support and environment, people can develop more effective professional relationships regardless of their traditional attachment style.

For business leaders, understanding these patterns offers valuable insights into team dynamics, conflict resolution, and professional development. It helps explain why some teams gel naturally while others struggle, and why certain management approaches work better with different individuals.

Understanding attachment styles in the workplace can help contribute towards explaining7 many common team challenges:

Communication Patterns: Team members with avoidant attachment styles might resist sharing information or struggle with vulnerability in team settings, potentially creating silos or hindering innovation.

Conflict Resolution: Those with ‘anxious attachment’ might avoid necessary confrontations or become overly defensive during feedback sessions, impacting the team's ability to address and resolve issues effectively.

Leadership Effectiveness: Leaders' attachment styles significantly influence their management approach. A securely attached leader typically creates psychological safety, while an avoidant leader might struggle to provide the emotional support their team needs.

Looking through the lens of attachment theory can help teams achieve more consistent performances

For example, a team member with a secure attachment style typically brings confidence, emotional stability, and healthy boundaries to their work relationships. They're comfortable with both independence and collaboration, making them natural team players.

In contrast, someone with an anxious attachment style might seek excessive validation, struggle with professional boundaries, or become overly dependent on colleagues' approval.

The Fit With Other Tools

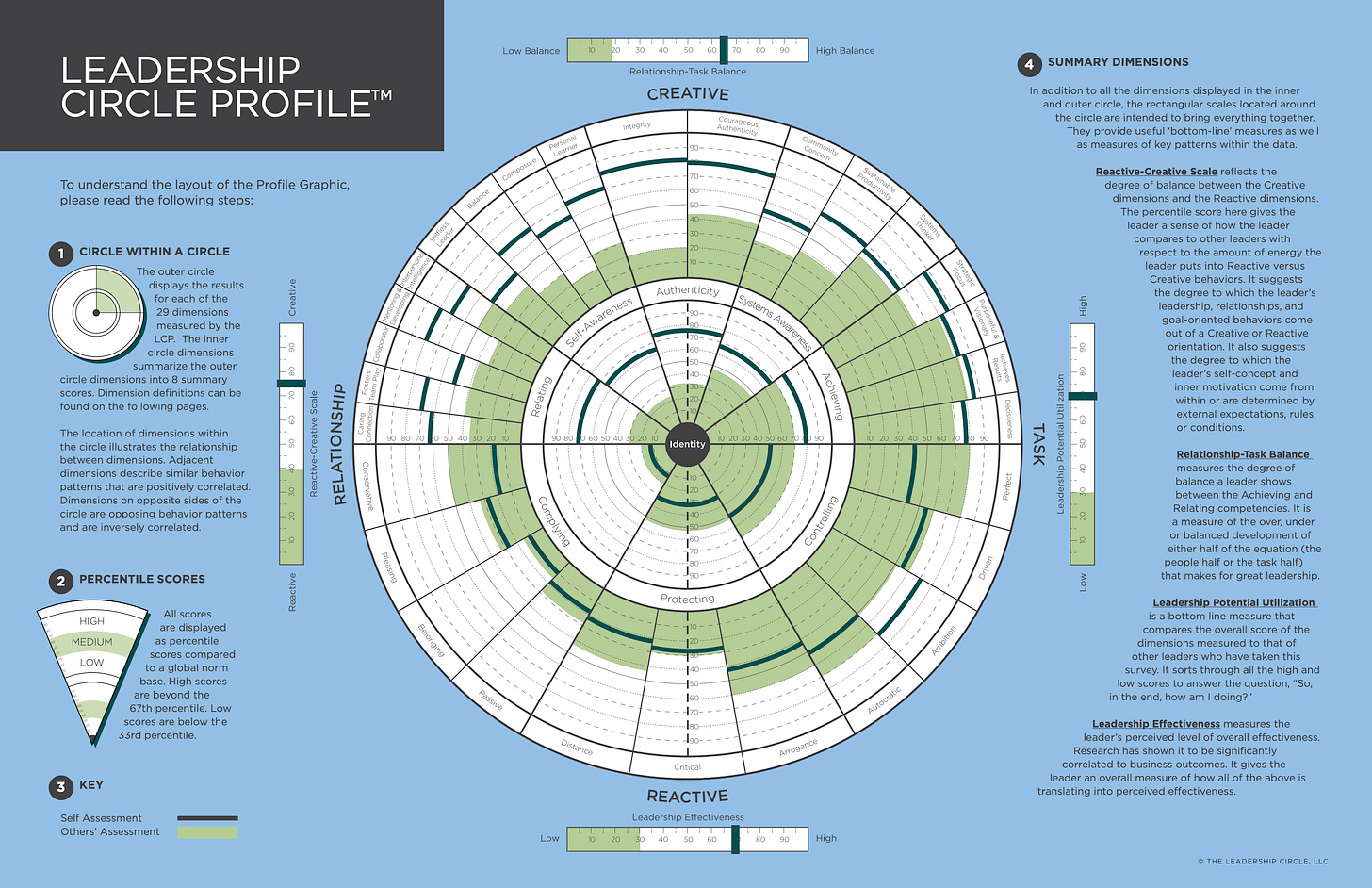

It is interesting to note the parallels between how attachment styles are expressed through behaviour and how the same behaviours are evidenced in the creative competencies and reactive tendencies found in the Leadership Circle Profile.

For example, excessive validation is most likely to be mirrored in the ‘Pleasing’ and ‘Belonging’ segments in the Reactive (lower half) of the Leadership Circle Profile.

Conversely, those with a secure attachment style are more likely to express behaviours found in the upper half of the Leadership Circle such as ‘Balance’, ‘Composure’, and ‘Fostering Team Play’.

Attachment theory appears to be a significant, yet often overlooked, factor in cultivating performance within teams. For example:

Leaders with high attachment anxiety tend to have self-serving leadership motives and poorer leadership qualities, negatively impacting followers' performance and mental health8.

Followers of anxious leaders report higher stress levels and lower job satisfaction9.

Leaders with high attachment avoidance are less likely to engage in prosocial leadership behaviours and fail to act as security providers, leading to poorer socioemotional functioning and long-term mental health issues for followers10.

Avoidant leaders are associated with lower organizational citizenship behaviours among followers and higher job burnout.

Transformational and relations-oriented leadership styles, which are often associated with secure attachment, positively influence followers' mental health and job performance11.

Securely attached leaders are more likely to exhibit pro-social and follower-empowering leadership styles, resulting in better leadership effectiveness and positive outcomes for followers12.

So What?

Attachment styles of leaders can profoundly affect their effectiveness and the well-being of their followers13. Similarly, research has suggested that in academic settings, secure attachments contribute to better academic performance by enhancing non-intellectual skills.

As always, there is a need to take a systemic perspective and the role that an organisation and/or team culture can play in influencing individual and collective behaviours.

The impact of leaders' attachment orientations on followers' outcomes can be moderated by cultural factors. For instance, in collectivistic cultures, avoidant leaders may have a more positive effect on followers' job satisfaction and emotional outcomes due to cultural norms around interdependence14.

Takeaways

Attachment theory provides a powerful lens for understanding and improving team performance. By acknowledging the role of attachment styles in workplace dynamics, organizations can create more effective, resilient, and harmonious teams.

Recognising and finding ways to use the insights that attachment theory provides offers leaders, managers and coaches additional ways to interpret and encourage individual and collective behaviours in ways that potentially enhance team performance outcomes.

[Thanks to Laurence Cassøe Halsted for the original inspiration for this article. You can read his take on attachment theory and its role in elite sports here].

Notes

The idea of seeing the spaces in between is a recurring theme throughout The Pocket Dojō. For a musical slant on this idea, you can cross-reference this post

Bowlby, J. (1978). Attachment theory and its therapeutic implications. Adolescent Psychiatry, 6, 5–33.

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1986). Discovery of a new, insecure-disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern. In M. Yogman & T. B. Brazelton (Eds.), Affective development in infancy (pp. 95–124).

Bartholomew K., Horowitz L.M. Attachment styles among young adults. A test of a four-category model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1991;61:226–244. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.2.226

This is true whatever lens or measurement tool is being applied in a given context.

It’s important to note that there is no direct causal relationship here only potential avenues for curiosity and enquiry.

Davidovitz, R., Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P., Izsak, R., & Popper, M. (2007). Leaders as attachment figures: leaders' attachment orientations predict leadership-related mental representations and followers' performance and mental health. Journal of personality and social psychology, 93 4, 632-50. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.4.632.

Kafetsios, K., Athanasiadou, M., & Dimou, N. (2014). Leaders' and subordinates' attachment orientations, emotion regulation capabilities and affect at work: A multilevel analysis ☆. Leadership Quarterly, 25, 512-527. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.LEAQUA.2013.11.010.

Ronen, S., & Mikulincer, M. (2012). Predicting employees' satisfaction and burnout from managers' attachment and caregiving orientations. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 21, 828 - 849. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2011.595561.

Mayseless, O. (2010). Attachment and the leader-follower relationship. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27, 271 - 280. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407509360904.

Ibid.

Not for this post but there is a need to clarify the debate around leaders and followers as most people, particularly educators, prefer the somewhat backward and damaging idea that leaders lead and attract followers. This is not the whole story and is something I will take up in a separate post.

Gruda, D., & Kafetsios, K. (2020). Attachment Orientations Guide the Transfer of Leadership Judgments: Culture Matters. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46, 525 - 546. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167219865514.